In our One Thing I've Learnt series, Entrepreneurs’ Forum ambassadors and honorary members reveal the one game-changing lesson they’ve learnt in their entrepreneurial journey. Providing a source of inspiration for anyone pursuing a similar path, our guest editors will share some of the critical business challenges they’ve faced and how they overcame them.

In this edition, Julian Leighton, founder of Orange Bus, talks about why ‘luck isn’t random’, the importance of taking opportunities when they present themselves and how to maximise them when they do.

Years ago I came across some research by Professor Richard Wiseman on why some people feel lucky and others don’t. In one of his most famous experiments, he gave both “lucky” and “unlucky” people a newspaper and asked them to count how many photographs were inside. On average, the unlucky people took about two minutes to finish, while the lucky ones took just seconds. Why? Because on the second page was a large message reading: “Stop counting – there are 43 photographs in this newspaper.” Most of the unlucky people missed it. For fun, Wiseman added another message halfway through: “Stop counting, tell the experimenter you have seen this and win $250.” Again, the unlucky people failed to notice it because they were still too busy counting photographs.

Wiseman concluded that so-called lucky people do four things: they stay open to opportunities, they follow their intuition, they turn bad luck into good, and they make the most of whatever comes along. That really resonated with me, because when I map that onto my own journey, it explains far more than the phrase “right place, right time”.

I’ve had what I’d definitely call unlucky breaks. At 18 I was into graffiti, got arrested, ended up in court and, not surprisingly, my A-levels fell off a cliff. I didn’t get into the London School of Economics like I’d been on track for – I went to Bradford and Ilkley Community College instead, which, with the best will in the world, isn’t quite the same thing. That could have been the moment I decided life had stitched me up. Instead, I found myself in a completely different scene – music, raves, putting nights on – where I learned, very fast, about taking risks, watching cash and even how to negotiate at three in the morning with a nightclub owner I owed £5,000 to. Not the syllabus LSE had in mind, but useful all the same.

A few years later, in corporate life, I hit another fork in the road. I was working for a meat trading company and the owner was, let’s say, not a leadership role model. One day, while I was on the phone trying to sort out a perfectly reasonable customer complaint, he started shouting and actually threw a phone at me, firing me after I tried to argue my case. I left, took him to court, and won – but the real win was the lesson: if I ever run a business, I will not treat people like that.

That apparently “bad” experience became one of the foundations of how we built Orange Bus years later – respectful, collaborative and a genuinely happy place to work. I very quickly landed a much better role – one I’d only gone looking for because I’d been fired. It was with an IBM Business Partner, a much more professional environment where I started to see how large-scale technology projects came together. I learned about building trust, managing risk, and handling multimillion-pound relationships over six-month sales cycles. It gave me a grounding in process, structure and scale that I’d later draw on constantly at Orange Bus. It also confirmed something important: I could operate comfortably in both worlds – the corporate and the entrepreneurial – and bridge the two.

Probably the biggest “this could have gone very differently” moment, though, was a scooter crash that put me in hospital for months. It wasproperly life-changing. But it was also the pause that made me ask: do I actually want to stay in corporate life? The answer was no. So I left, did a master’s, bought an old VW campervan and started doing bits of digital consultancy. Driving around in that orange van, I became known as “Julian with the orange bus”, which eventually became “Orange Bus” the company. That wasn’t a 15-year strategy – it was me noticing that people remembered the van, journalists wanted to photograph it, and clients liked the story. So we built on it.

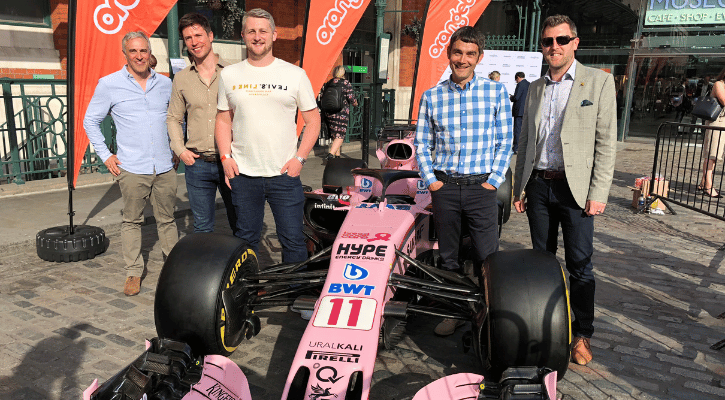

And that, I think, is the real point: luck often shows up looking like hassle. A breakdown. A setback. A conversation you weren’t planning to have. Here’s the best example I’ve got. One day the campervan conked out on the Coast Road. Not a graceful stop either – middle lane, people glaring at me as they passed. Nearly everyone drove on, only one person stopped: a young racing driver called Harry Vaulkhard. We chatted while we waited. I offered to build him a website as a thank you. He put our logo on his car. Then he started winning – first he won the SEAT Cupra Championship, then he moved into the British Touring Car Championship, then into Europe. Because we’d backed him early, we went with him. That got us into motorsport and we were able to move into bigger teams and different championships. From there we ended up working with Aston Martin Racing, Porsche Motorsport and, eventually, Formula One. If I’d just sat there moaning about old VW vans and said “thanks mate” when Harry pushed me to safety, none of that would have happened. People call that luck. I call it spotting an opening and doing something with it. Orange Bus went on to become one of the UK’s leading digital agencies, and in 2016 we sold the business to a FTSE 100 PLC. I joined the board of their software business and spent the next few years helping integrate multiple acquisitions. It was a fascinating experience seeing how large corporations plan and operate, and how very not entrepreneurial they can be.

Everything was forecast in advance, with little room to deviate either way – no matter how positive or negative the outcome. For someone used to working in an environment fuelled by experimentation and momentum, it was an education in contrast. As Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, writes in ‘Let My People Go Surfing’, entrepreneurs don’t always need the perfect plan – sometimes you take a step towards the opportunity, see how it feels, then take another. If it still feels right, you keep going, if it doesn’t, you step back. That is exactly how so much of my career has gone. We didn’t sit down and forecast our way into working with global motorsport brands or a FTSE 100 boardroom; we saw a door open and we walked through it.

So if there’s one thing I’ve learnt, it’s this: luck isn’t just about what happens to you – it’s about how available you are to it. Most people are heads-down, counting the photographs in the newspaper, to use Wiseman’s experiment, and they miss the line on page two that basically says: “You can stop now. The opportunity’s here.” Entrepreneurs can’t afford to miss that line. We have to keep our heads up. There’s a quote often attributed to Winston Churchill that I’ve had in my head since I was young: “During their lifetimes, every man and woman will stumble across a great opportunity. Sadly, most of them will simply pick themselves up, dust themselves down and carry on as if nothing ever happened.”

My experience – from campervans to corporate boardrooms – is that the entrepreneurs who do well are simply the ones who don’t brush themselves down and carry on. They pause, they notice, and they ask: “What can I do with this?” That’s not magic. That’s a habit. And it’s the closest thing to luck I know.